She had not anticipated its roughness, the brush-burn it left in its wake across her skin. It dwarfed and outmatched her, this yellow thing. How was she supposed to control it, let alone ride it?

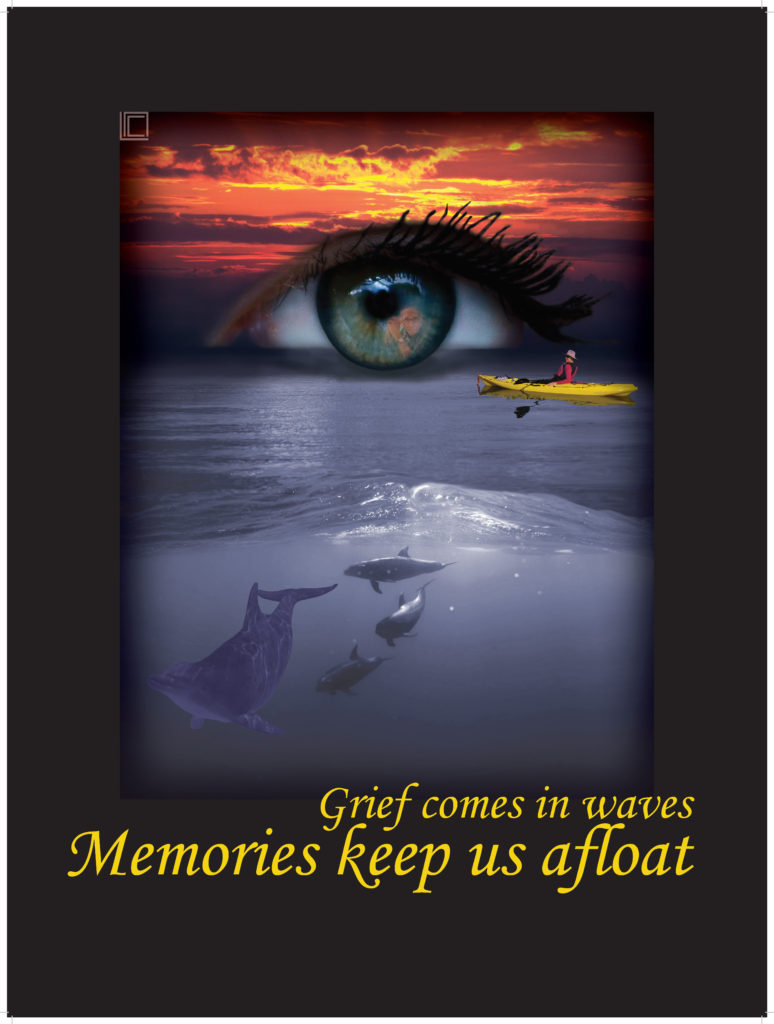

Sand swirled around my heels, rising up to my ankles. The weight of the banana-boat monstrosity—ahem, kayak—wedged me further into the shore as I tried to haul it out of the quicksand, against the tide into open waters. The struggle of wills cut short as a wave lazily wrapped around the kayak in a gentle hug, coaxing it fully into the salty bath of the Outer Banks. Surprised by the sudden change to weightlessness, I lost my balance. A hand steadied me before I could fall. My Uncle Bryon’s voice carried easily over the crashing foam around us, “Hop in, and paddle out. Just don’t ride parallel to shore until you’re past the waves.” He held the yellow kayak steady in the thigh-deep combination of water, salt, and fish pee. Ever the eager Labrador, I hopped in. The transition from solid ground to fluid surface was immediate; the boat pitched and rolled, a bucking bronco with one master—the sea. Luckily for me, Uncle Byron owned the sea, and likewise the bronco. He guided me through each wave until we were beyond the breaking point, the sounds of the beach fading into a distant roar behind us. Then, he let go. I will never forget that day, that moment, that yellow kayak; it became the embodiment of my uncle—his adventurousness and his legacy—when he let go for the final time.

She was six with the courage of twenty. Adult hands shackled her in place, forcing her to watch from the sidelines, imagining what it must be like to be her uncle—to be a pirate.

Pirates have yellow toes, therefore Byron was a pirate; he would have made a better adventurer than Blackbeard himself. Every year, my uncle rented that yellow kayak. And every year, he was the only one to ride it out to sea. I watched in awe as he navigated the swells with ease, disappearing into a dot, and then returning full-size. One year, Byron managed to convince my dad to go out in it—but never again. The wave was mountainous. My dad stood no chance. His kayak went under, and so did he—adding another ten years to my imprisonment for protection from danger. However, such a silly thing as “danger” did not stop my uncle. He continued his annual voyage to the horizon, while I manned the pirate kite. It soared high into the cloudless sky, taunting the sun with its dancing tail. If it fell, my uncle would not be able to find his way back home. So, I stayed and manned the kite, the lighthouse, knowing one day it would be my turn to be a pirate.

The soft pitters crescendoed towards her, silver fish jumping over her, flicking her with ocean rain. Quiet shapes streamed after them, crossing under her boat—dolphins. What other life went unseen to her eyes?

Cancer is yellow; and just like the kayak was returned to its owner, so was my uncle. Esophageal cancer patients have a survival rate of about 18%, until the cancer spreads to other parts of the body—dropping the rate to 5%. From 2015-2017, cancer was a fake curse on a fortified kingdom. How could something so measly conquer my uncle, the Kayak King? The answer, obviously, was never. So, I went off to college believing that he would survive, that I would get to see him again in all his regal glory. Three days after my departure, the kite fell—Byron did not find his way home.

She could die—capsize and drown. She was at nature’s mercy, alone in the middle of the ocean. Sunlight beat on her cheeks, snapping her out of her reverie, pressing the play button of life.

Kayaks are yellow; so let’s just say my uncle became my kayak. He carried all of us in his own way, offering liberal doses of sarcasm and advice. Byron singlehandedly crafted traditions that defined who my family was, stepping into roles that could only be filled by a living grouch like him: doctor, parent, party king, “Father Christmas.” Going to the Outer Banks together as a family was his ultimate tradition; he and my father made sure it happened every year without fail. And somehow, he still made time to make his own adventurous traditions, like the yellow kayak—always yellow, never orange or blue. Cancer was the hole in his boat, yet he still lived life to the fullest—making the most of what life dealt him.

And with a deep sigh, she headed back to shore. Little did she know that the ocean stole a part of her through that final breath, claiming it forever.

I don’t know if I will ever again ride a yellow kayak on the open waters of the Outer Banks. I don’t know who will be with me when the time comes, or who will be gone. My family is old. So, death has always been something I accepted. However, I felt robbed by my uncle’s death—he left too soon. Supposedly, a “changed self emerges” from intense grief as a person is forced to move into an unanticipated future. I definitely feel like a change has transpired within me, but I’m afraid it’s not for the better. Losing Uncle Byron derailed me. I don’t know how long I need to recover, or if I will ever return to the bright, fearless adventurer I once was. All I know is that my uncle was a pirate, and the kayak was his vessel. And that will never change. Because, kayaks are yellow.